Don't Chase the Warning!

As you enable the C# 8 Nullable Reference Types feature, you may find that applying the ? and ! type hints isn’t enough. You may see that the compiler needs a few extra clues in order to make accurate conclusions about your code. Thankfully, a number of special attributes are available for further describing the nullability of method parameters and return types.

As we saw in Nullable Reference Types in Entity Framework, the Nullable Reference Types feature allows us to write largely null-free code, using compiler warnings to alert us to the limited null values that we do have to care about. Distracting null checks go away, while meaningful null checks come to the forefront. Variable, parameter, and return type declarations are assumed to be never-null unless they are marked as nullable, allowing the compiler to call out apparent contradictions. Three rules cover most scenarios:

TypeName variable- A variable, parameter, or return type is assumed to be never-null by default.TypeName? variable- A variable, parameter, or return type can be marked as possibly-null.expression!- If the compiler determines an expression is possibly-null, but you know that it really won’t be in practice, you can assert that with the “null forgiveness” operator:!

However, while applying the Nullable Reference Types feature to the Fixie test framework, I found that merely applying the ? and ! type hints wasn’t quite enough to express the truth about my code. Today, we’ll follow the train of thought from an initial warning message, to a partial solution, to some surprising warnings, and finally reach a complete solution by applying the [NotNullWhen] attribute.

Enlisting Listeners

First, some background. As your test suite runs, Fixie emits events (This Test Passed!, This Test Failed!, …), and these events are handled by one or more interested parties called “Listeners”. Listeners correspond with the test reporting system that you’re using. If you’re running on Azure DevOps, for instance, then the AzureListener responds to each event by including them in your build’s “Tests” report screen. If you’re running on TeamCity, then the plain old console output gets modified by TeamCityListener into a format that TeamCity can process for its own report. Before your tests run, we enlist applicable Listeners:

static IEnumerable<Listener> DefaultExecutionListeners(Options options)

{

if (Try(AzureListener.Create, out var azure))

yield return azure;

if (Try(AppVeyorListener.Create, out var appVeyor))

yield return appVeyor;

if (Try(() => ReportListener.Create(options), out var report))

yield return report;

if (Try(TeamCityListener.Create, out var teamCity))

yield return teamCity;

else

yield return new ConsoleListener();

}

static bool Try<T>(Func<T> create, out T listener)

{

listener = create();

return listener != null;

}

Analyzing simple nullability warnings

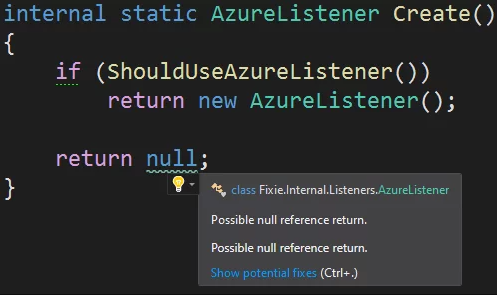

When I first turned on the C# 8 “Nullable Reference Types” feature, I wasn’t too surprised to see some warnings in these many Create methods, because they either return a useful instance or null:

Here, the compiler is claiming that we’re being inconsistent about nulls. The method is declared to return an implicitly-never-null AzureListener instance, yet we’re clearly contradicting ourselves with an explicit return null. This kind of warning is pretty typical when you first enable Nullable Reference Types: old code is littered with examples that suddenly become contradictions in the eyes of the extra strict compiler.

In this case, the right move is simple. We really do want this method to occasionally return null: that’s exactly how it announces that no AzureListener is applicable. The Try method, seen above, is responsible for dealing with that possibility. We resolve this warning by simply telling the truth, marking each Create method with a nullable (?) return type:

internal static AzureListener? Create()

{

if (ShouldUseAzureListener())

return new AzureListener();

return null;

}

Analyzing Complex Nullability Warnings

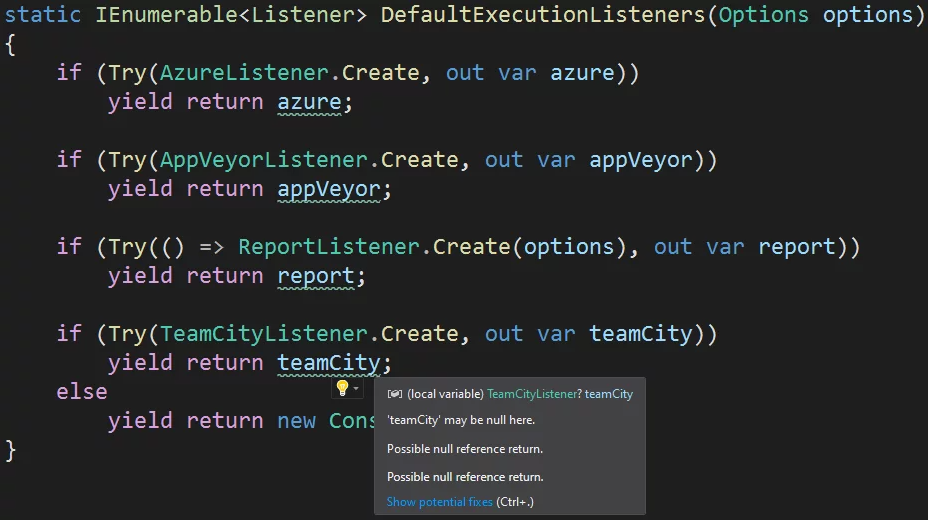

Upon rebuilding, my list of warnings was just as big as before! We addressed the warnings within each Create method, but new warnings pop up back where they’re being used:

It took some time to realize what was going on here. We must think like the compiler. The first argument we pass to Try is AzureListener.Create, which we just said is a function that returns a sometimes-null AzureListener?, so in this invocation of Try, the T type parameter is replaced with AzureListener?. That means our out parameter T is also an AzureListener?, and so must be the azure variable in our first yield return.

Our warnings on every yield statement begin to make sense. Every time we try to yield an instance returned by one of these Create methods, we get a warning: that Listener might be null, like we just declared in each Create method, but DefaultExecutionListeners is declared to yield zero or more non-null listeners.

Because we know how each Create method is really implemented, we can sit back and think really hard and convince ourselves that we’ll never really arrive at the yield statements with a null value. But the compiler isn’t convinced. All it sees is a blatant contradiction.

A Natural Pitfall

The single biggest mistake people are going to make when using Nullable Reference Types is to quickly “chase” the warning message, taking it too literally, without stopping to think through the larger context. The first warning motivated us to place ? hints where the compiler wanted us to. If we just do the same here without thinking, though, we would create a growing problem:

static IEnumerable<Listener?> DefaultExecutionListeners(Options options)

{

...

}

This lackluster attempt satisfies the warning, but propagates a lie. We know the IEnumerable will never contain a null, but we’re saying it will. The code that calls DefaultExecutionListeners would have to handle nulls that never happen, and the code that calls that would have to handle nulls that never happen. You’d “chase” the warning messages all over your project. Before long, our entire codebase would be littered with inaccurate question marks just to make the compiler stop complaining. We’d end up with code equivalent to C# 7 where we didn’t have Nullable Reference Types at all, except now we’d be worse off, explicitly telling developers that something is meant to be nullable when it isn’t in fact. Madness! We need a different solution.

Solution: Declare Conditional Nullability

Instead, we can satisfy the compiler without propagating lies, by telling the compiler about the relationship between our bool return value and our nullable out parameter. Let’s fully describe the nullability of the Try method. Our understanding that we would never yield a null comes from our understanding of the bool value returned by Try. When it returns true, we know that our out parameter is not null. If the compiler knew that fact as well, then it could conclude that we’d never reach the yield statements with null values. Thankfully, there are a number of nullability attributes for describing the conditional nullability of our methods’ inputs and outputs. We improve the Try method by saying, “Sure, the out parameter can be null sometimes, but not when Try returns true!” We do so by using the [NotNullWhen(true)] attribute:

static bool Try<T>(Func<T> create, [NotNullWhen(true)] out T listener)

{

listener = create();

return listener != null;

}

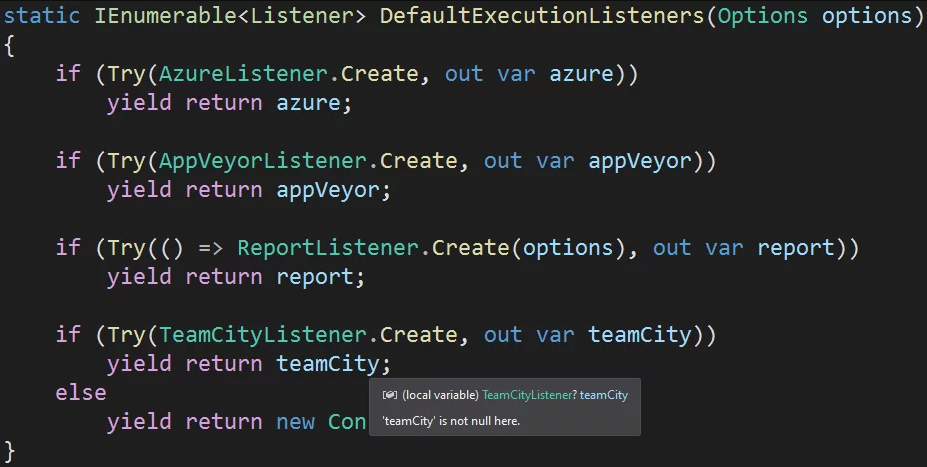

Now, the compiler has as much information as we do. It now knows of the relationship between Try’s bool return value and the actual nullability of the out parameter. Since the yield statements appear within the true branch of the if statements, it knows they’re not null by that point and will stop suggesting that we propagate ? modifiers through the entire system. No more misleading warnings:

Conclusion

The purpose of the Nullable Reference Types feature is to discover probable bugs while avoiding excessive null checks. For the feature to be effective, though, we need to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth about the nullability of our identifiers. If we stray from that truth-telling ideal, our systems will be covered in misleading type hints and we’ll find ourselves falling back on old-fashioned techniques for dealing with nulls. If we stick to our principles, reacting to each warning purposely and with a clear understanding of why we’re being warned, we can keep our code clean and understandable as well as correct.