Meaningful Test Coverage

Your tests come with a glowing code coverage report, but I’m not convinced. A subtle rot spreads through your tests without you even knowing it: your tests keep passing, and your code coverage report keeps claiming health, but in fact your tests drift further and further away from demonstrating the system’s true behavior. Thankfully, we can fight back by identifying the root cause of this rot and by addressing it with a simple assertion method.

Naive integration tests

Consider a basic Contact List application that tracks the names and email addresses of your contacts. We’d develop the Edit Contact feature along with an integration test: one that invokes the feature and confirms the behavior, all the way out to a real database. The test would begin by invoking the Edit Contact feature for a sample Contact and querying the database for the updated Contact’s actual state. We’d finish the test by asserting on the Contact’s individual properties, demonstrating all the expected updates took hold:

actualContact.Id.ShouldBe(contactId);

actualContact.Name.ShouldBe("Sue Smith");

actualContact.Email.ShouldBe("sue.smith@example.com");

The rot sets in

This is great, but only for the next few hours. The next day, your teammate works to add a new PhoneNumber property to the Contact entity. They diligently visit features like Add Contact and Edit Contact to make use of the new property, but they aren’t yet comfortable with maintaining test coverage, so they aren’t even aware of your integration test. They do know to modify the Edit Contact feature to set PhoneNumber, and they even run the build. The integration test has quietly become incomplete, but it still passes.

Your teammate thinks they’re done, but they’ve taken the first step on the path to subtly eroding the value of your system’s test coverage. The test is lying, the code coverage report is lying, and developers will come to distrust the growing set of passing-yet-incomplete tests.

The root of the problem is the reliance on field-by-field assertions. Our intent was to assert on the new state of the system, but that is not what the test is doing. You have to keep on remembering to reevaluate your tests every time you make a change to the system, and inevitably forget.

Expressing intent with ShouldMatch

The integration test’s entire reason for being is to demonstrate the true and complete effect of the Edit Contact feature. In a perfect world, our poor teammate would not have to be aware of the existing test. Instead, we’d rather have the system tell them right away that their work is not finished. We can do so by defining our own assertion helper, ShouldMatch, and an exception for describing mismatched objects:

using System.Text.Json;

public static class TestHelpers

{

public static string Json(object value) =>

JsonSerializer.Serialize(value, new JsonSerializerOptions

{

WriteIndented = true

});

public static void ShouldMatch<T>(this T actual, T expected)

{

if (Json(expected) != Json(actual))

throw new MatchException(expected, actual);

}

}

using static System.Environment;

using static TestHelpers;

public class MatchException : Exception

{

public object Expected { get; }

public object Actual { get; }

public MatchException(object expected, object actual)

: base(

$"Expected two objects to match on all properties.{NewLine}{NewLine}" +

$"Expected:{NewLine}{Json(expected)}{NewLine}{NewLine}" +

$"Actual:{NewLine}{Json(actual)}")

{

Expected = expected;

Actual = actual;

}

}

Here, we get a plain text representation of our complete objects for comparison, using the new JSON support in .NET Core 3. Next, we rephrase our original naive assertion:

actualContact.ShouldMatch(new Contact

{

Id = contactId,

Name = "Sue Smith",

Email = "sue.smith@example.com"

});

This solves the immediate problem. The moment the developer adds PhoneNumber support to the Edit Contact feature, this test will begin to (rightly!) fail. The test fails because the developer hasn’t updated the test to match the true behavior of the system. Some would say this is a brittle test, misapplying general advice about tests failing easily in a way that doesn’t carry meaning. Keep in mind that if this simply remained green instead, it would now be wrong and green, which is worse than temporarily red and reminding me of the full impact of my changes. Let’s be sure that we’re optimizing for correctness in the face of human fallibility instead of for greenness.

Enhancing ShouldMatch With Your Diff Tool

ShouldMatch lets us better-express our intent, but the test will fail with a rather lengthy message, listing two large JSON strings. The developer has to eyeball where the strings differ.

To give the developer a fantastic development experience, telling them exactly what’s wrong with the test, we’ll modify our test runner’s own behavior. Using the Fixie test framework, we’ll define a convention: whenever the developer is running a single test, if the test fails due to a MatchException, launch the developer’s own diff tool with the Expected and Actual JSON strings:

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.IO;

using Fixie;

using static TestHelpers;

public class TestingConvention : Execution

{

public void Execute(TestClass testClass)

{

testClass.RunCases(@case =>

{

var instance = testClass.Construct();

@case.Execute(instance);

var methodWasExplicitlyRequested = testClass.TargetMethod != null;

if (methodWasExplicitlyRequested && @case.Exception is MatchException exception)

LaunchDiffTool(exception);

});

}

static void LaunchDiffTool(MatchException exception)

{

var diffTool = Configuration["Tests:DiffTool"];

var tempPath = Path.GetTempPath();

var expectedPath = Path.Combine(tempPath, "expected.txt");

var actualPath = Path.Combine(tempPath, "actual.txt");

File.WriteAllText(expectedPath, Json(exception.Expected));

File.WriteAllText(actualPath, Json(exception.Actual));

using (Process.Start(diffTool, $"{expectedPath} {actualPath}")) { }

}

}

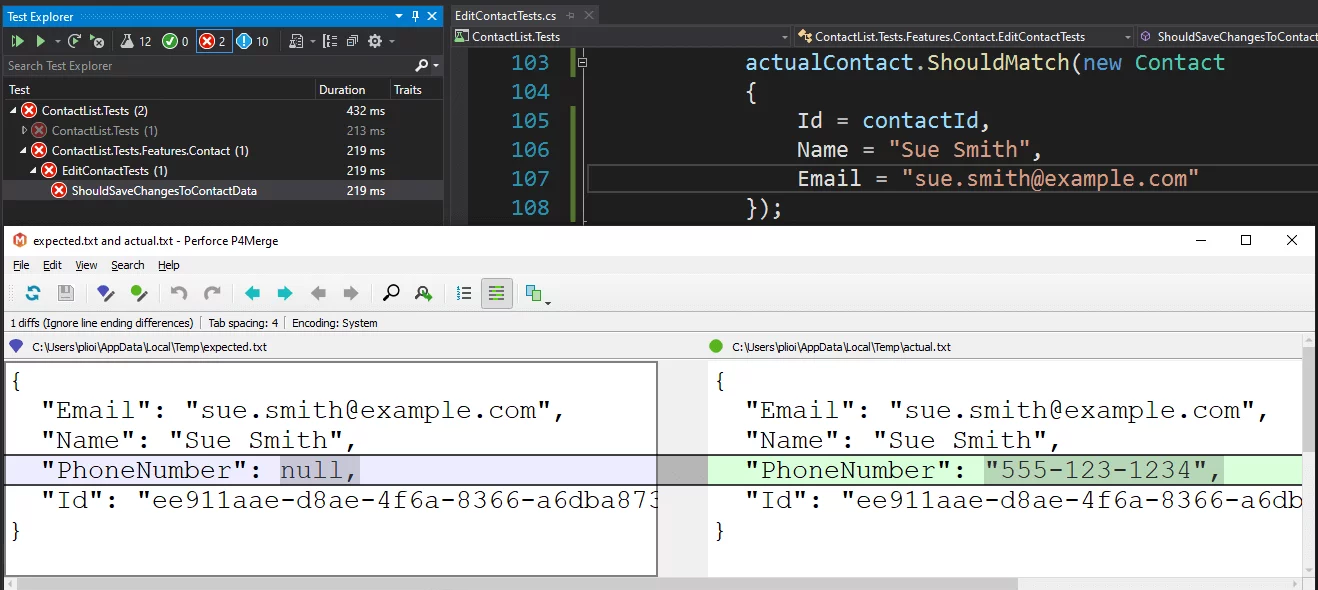

With this infrastructure in place, the developer updates the Edit Contact feature, witnesses a surprising test failure right away, and then upon running that test in isolation, they see this:

The test is telling the developer that their job isn’t done yet, with exactly the guidance they need to finish the job, maintaining meaningful test coverage by default. For all those out there with a glowing code coverage report, ask yourself: How much of this coverage is even real?