Whittling Parsley

A few weeks back, I introduced the idea of Code Whittling, in which you actively remove code from an unfamiliar project in order to learn about it and discover its most interesting core functionality. I used this technique to learn about 3 open source projects: Rhino Licensing, xUnit, and NUnitLite. I’ve got one more open-source project I’d like to apply this to, but in a Shyamalanian twist I’ll use this approach to teach something about one of my own projects, instead of using it to learn about someone else’s project.

I’ve written about Parsley here before: it’s a library that lets you declaratively parse complex text patterns, like a super-duper regex. This week, we’ll tear this project down to get to the nuts-and-bolts of text traversal and pattern recognition, and next week we’ll rebuild some of the layers destroyed along the way. We’ll discard the high-level useful bits this week, revealing a simple-yet-frustratingly-verbose core, so that next week we can reintroduce the layers that make it ultimately useful and terse. We can make an analogy with C versus assembly: you don’t want to write assembly, even though that is the truth happening under the surface, but you’ll better-understand C once you’ve seen assembly.

A Little Background

If .NET didn’t already have an excellent JSON parsing library, for instance, and someone needed your app to inspect and make use of some JSON as input, you might first reach for some kind of enormously complex regex, only to run into trouble describing the recursive nature of JSON (JSON objects can contain JSON objects (within JSON objects (within JSON objects))). Regexes aren’t quite powerful enough to describe such patterns, and even if a complex regex is enough to handle your parsing needs, interpreting the results of a regex with multiple returned groups can be tedious.

Instead, you could use a library like Parsley to simply describe what a valid JSON string looks like, as well as describe how each part of JSON corresponds with your own classes. Then, the library does the heavy lifting for you. For instance, Parsley’s integration tests contain a JSON parser which produces .NET bools, decimals, strings, arrays, and dictionaries when given an arbitrary JSON string as input.

Parsley is an internal DSL for creating external DSLs, so the normal use case involves simply declaring what successful input looks like, at a high level:

//Excerpt from JsonGrammar.cs

Number.Rule =

from number in Token(JsonLexer.Number)

select (object) Decimal.Parse(number.Literal, NumberStyles.Any);

Quotation.Rule =

from quotation in Token(JsonLexer.Quotation)

select Unescape(quotation.Literal);

Array.Rule =

from items in Between(Token("["), ZeroOrMore(JsonValue, Token(",")), Token("]"))

select items.ToArray();

Pair.Rule =

from key in Quotation

from colon in Token(":")

from value in JsonValue

select new KeyValuePair<string, object>(key, value);

Dictionary.Rule =

from pairs in Between(Token("{"), ZeroOrMore(Pair, Token(",")), Token("}"))

select ToDictionary(pairs);

JsonValue.Rule = Choice(True, False, Null, Number, Quotation, Dictionary, Array);

High-Level Architecture

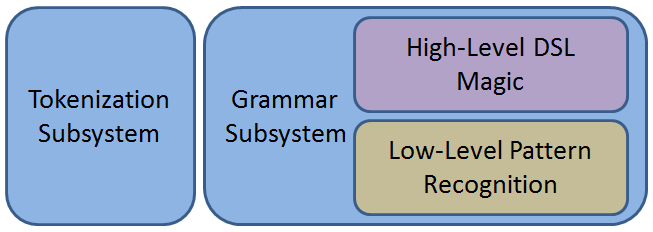

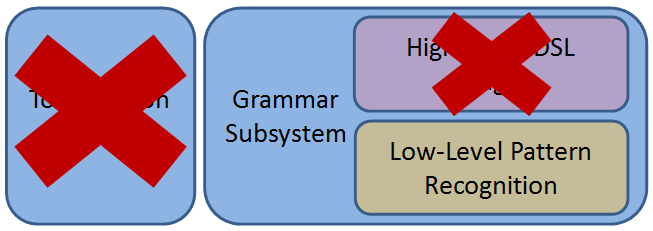

Parsley can be broken down into 2 distinct subsystems: tokenization and grammars. The grammar subsystem includes a low-level means of processing the input as well as a high-level DSL to make it all pretty like the example above.

In a tokenization phase, a JSON string like “[1, 10, 100]” is chopped up into a series of substrings: “[”, “1”, “10”, “100”, and “]”. Note that tokens can be multiple characters, as long as they represent a single meaningful thing in JSON. A token could be an operator, a keyword, a number, or a whole quoted string literal. Cutting any of these things into a smaller substring would remove its meaning, so we say “that’s small enough” and stop there. We also remember what kind of token each substring is, so in our example the tokenizer really turns “[1, 10, 100]” into (“[”, OpenArray), (“1”, Number), (“,”, Comma), (“10”, Number), (“,”, Comma), (“100”, Number), (“]”, CloseArray).

This collection of token objects is then handed off to the second subsystem, in which a grammar for our language is declared. Parsley takes the collection of tokens, applies the grammar to it, and out pops plain old .NET objects like arrays, dictionaries, or instances of your own classes.

My goal today is to reveal that low-level processing within the grammar subsystem. To get there, we’re going to have to whittle away a most of the project:

The Whittle - Removing the Tokenizer Subsystem

I started by creating a new clone of https://github.com/plioi/parsley.git.

As with the last three weeks, the first thing I got rid of was the unit testing project. We’re about to start throwing away things left and right, and the tests were just going to be in the way.

Next, I focused on removing the entire tokenization subsystem. I deliberately made it so that you could use the grammar subsystem without the tokenizer subsystem. There are very real reasons why the default tokenizer wouldn’t be enough for your needs: Python’s significant indentation, for instance, requires that you maintain some extra state and make some extra decisions along the way just to produce meaningful tokens. Since I wanted a simple tokenizer that would work for most people, and also wanted to leave the door open for Python-style gymnastics, you can provide your own drop-in replacement tokenizer: anything that produces a collection of Token objects will satisfy the grammar subsystem.

Tokenizing isn’t the interesting part. If we inspect the next few characters in the input, surely we can decide whether we’re looking at a word, or an operator, or whatever. We could go through the details, but it wouldn’t be surprising or enlightening. To kill off the default tokenizer, I removed several classes we can ignore for the rest of today’s discussion: I dropped Lexer, which does the string-chopping action, as well as some classes that lived only to serve Lexer.

At this point, the tokenizer subsystem was dead, may it rest in pieces.

The Whittle - Removing the DSL

This left me with the right-hand side of the archtecture diagram above. Time to whittle away anything that contributes to the high-level DSL seen in the JSON example grammar above. I won’t belabor the point by listing all the classes that got removed in this step. We’ll revisit them next week when we see how they build on top of the low-level pattern recognition code.

Core Pattern-Recognition Classes

Only a few classes survived this attack, representing the bottom-right portion of the architecture diagram.

Token - Recall that the tokenizer subsystem’s job is to turn the input string into a collection of these Token objects. They are our input. It’s easier to work with these than to work with the original raw input string. A token is a string like “100”, a position like “row 1, col 3”, and a TokenKind like “Number”:

public class Token

{

public TokenKind Kind { get; private set; }

public Position Position { get; private set; }

public string Literal { get; private set; }

public Token(TokenKind kind, Position position, string value)

{

Kind = kind;

Position = position;

Literal = value;

}

}

Position - This class is a pair of integers representing the line # and column # that a token was found at. It inherits from Value, which just provides a basic equality and GetHashCode implementation:

public class Position : Value<Position>

{

public int Line { get; private set; }

public int Column { get; private set; }

public Position(int line, int column)

{

Line = line;

Column = column;

}

}

TokenKind - When you use Parsley to define your tokenizer phase, you provide a list of TokenKind objects. If you’re making a JSON parser, you create an instance for each operator, each keyword, one for Number, one for Quotation… Each TokenKind also knows how to recognize itself in the raw input; a TokenKind representing variable names in the language you are parsing will be able to look at the raw input and say “Yes, the next 6 characters are a variable name,” or “Nope, the next few characters are not a variable name.” Since the string-recognizing methods are irrelevant outside of the tokenizer phase, I’ve omitted them here:

public abstract class TokenKind

{

public static readonly TokenKind EndOfInput = new Empty("end of input");

public static readonly TokenKind Unknown = new Pattern("Unknown", @".+");

private readonly string name;

protected TokenKind(string name)

{

this.name = name;

}

public string Name

{

get { return name; }

}

}

TokenStream - Admittedly weird, TokenStream takes the arbitrary collection of Tokens produced by the tokenizer subsystem and presents them to the grammar subsystem in a way that provides traversal without needing state change. If you ask this to advance to the next token, the object doesn’t change; instead you get a new TokenStream representing everything except for the token you are advancing beyond. This action resembles the Skip(int) IEnumerable extension method. Rather than dwell on the weird implementation, it’s easier to just see its usage within TokenStreamTests. When you have a TokenStream containing the tokens “[”, “10”, and “]”, and you call .Advance(), you’ll get a TokenStream containing only the tokens “10” and “]”.

Parser, Reply, Parsed, and Error - These are our fundamental building blocks. A Parser is anything that consumes some Tokens from the stream and produces a Reply. A Reply is either successful (Parsed), or unsuccessful (Error). When successful, a Reply holds a Value, the .NET object you wanted to pull out of the original plain text. Successful or not, the Reply also holds a reference to the remaining, not yet consumed Tokens. A Reply basically says “I worked, and now we’re here,” or “I failed, and we’re still there.” The whittled and simplified versions of these classes appear below:

public interface Parser<T>

{

Reply<T> Parse(TokenStream tokens);

}

public interface Reply<T>

{

T Value { get; }

TokenStream UnparsedTokens { get; }

bool Success { get; }

}

public class Parsed<T> : Reply<T>

{

public Parsed(T value, TokenStream unparsedTokens)

{

Value = value;

UnparsedTokens = unparsedTokens;

}

public T Value { get; private set; }

public TokenStream UnparsedTokens { get; private set; }

public bool Success { get { return true; } }

}

public class Error<T> : Reply<T>

{

public Error(TokenStream unparsedTokens)

{

UnparsedTokens = unparsedTokens;

}

public T Value { get { throw new MemberAccessException(); } }

public TokenStream UnparsedTokens { get; private set; }

public bool Success { get { return false; } }

}

The Result - Tedious Pattern Recognition

These classes don’t look like much, and their emphasis on zero-state-change is atypical for .NET development, but when combined they let us deliberately walk through the input Token collection, recognizing patterns along the way.

Let’s consider a simple example. We want to be given a string and then decide whether or not it is a parenthesized letter like “(A)” or “(B)”. If we’re given “(“, “(A”, “(AB)”, or “Resplendent Quatzal”, then we want to report failure. Sure, we could do this with a regex, but any simple example could work with a regex. I only need an example complex enough to show how these Parser/Reply/TokenStream classes work together.

Let’s assume we’ve implemented our tokenizer phase correctly already. The tokenizer phase defined 3 TokenKind instances:

TokenKind LeftParen = new Operator("(");

TokenKind Letter = new Pattern("Letter", @"[a-zA-Z]");

TokenKind RightParen = new Operator(")");

The tokenizer hands us the tokens to evaluate:

//Assume the tokenizer has produced these tokens from the string "(A)":

var resultFromTokenizerPhase = new[]

{

new Token(LeftParen, new Position(1, 1), "("),

new Token(Letter, new Position(1, 2), "A"),

new Token(RightParen, new Position(1, 3), ")")

};

We want to write a function which receives these Token objects and tells us whether or not it is a parenthesized letter. If it is, we want to report what the letter was. If it isn’t, we want to tell them exactly what went wrong. Before we do that, we’ll need to provide a useful implementation of the Parser

public class RequiredTokenParser : Parser<string>

{

private readonly TokenKind expectedKind;

public RequiredTokenParser(TokenKind expectedKind)

{

this.expectedKind = expectedKind;

}

public Reply<string> Parse(TokenStream tokens)

{

//Succeed when the next token is of the expected kind,

//advancing to the next token. The successful value

//to return is the literal text within the token.

if (tokens.Current.Kind == expectedKind)

return new Parsed<string>(tokens.Current.Literal, tokens.Advance());

//Oops, we didn't see what we expected. Fail without advancing.

return new Error<string>(tokens, ErrorMessage.Expected(expectedKind.Name));

}

}

...

public static Parser<string> Require(TokenKind kind)

{

return new RequiredTokenParser(kind);

}

Finally, we have enough to write IsParenthesizedLetter(Token[]):

public string IsParenthesizedLetter(Token[] resultFromTokenizerPhase)

{

var tokens = new TokenStream(resultFromTokenizerPhase);

var replyA = Require(LeftParen).Parse(tokens);

if (replyA.Success)

{

var replyB = Require(Letter).Parse(replyA.UnparsedTokens);

if (replyB.Success)

{

var replyC = Require(RightParen).Parse(replyB.UnparsedTokens);

if (replyC.Success)

return string.Format("Parenthesized {0}!", replyB.Value);

return string.Format("Expected {0} at {1}.", RightParen, replyC.UnparsedTokens.Position);

}

return string.Format("Expected {0} at {1}.", Letter, replyB.UnparsedTokens.Position);

}

return string.Format("Expected {0} at {1}.", LeftParen, replyA.UnparsedTokens.Position);

}

Phew! That is monotonous. Writing this is nearly as tedious as writing assembly. Each time I wanted to progress a little further, I had to indent again and declare some new local variables. I had to carefully pass along the remaining unparsed tokens at each step, and I had to concern myself with failure at each step.

To make matters worse, this stuff motivates having lots of returns from a single function, making it extremely hard to break the function apart into smaller parts. Return statements are “Extract Method” fences.

Consider, though, that if we wanted to concern ourselves with concepts like “the next token has to be either a Foo or a Bar or a Baz”, we could use this approach to “test the waters” as we go: Require(Foo) and if the reply was a failure, just Require(Bar) using the same original TokenStream, and if that reply is a failure just Require(Baz) again using the same TokenStream. We get backtracking for free without having to take on the dangers of tracking some global, writable int represting our progress through the token array.

With all the downsides, allowing backtracking in this manner doesn’t seem very worthwhile, but writing in assembly doesn’t seem very worthwhile either.

Next week, we’ll see how we can build a more useful, declarative API on top of these low-level pattern recognition primitives. The suspense is killing you!